Quetiapine Fumarate

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use QUETIAPINE TABLETS safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for QUETIAPINE TABLETS. QUETIAPINE tablets, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 1997

132a2483-7e49-4b0c-9db4-e6e578697fd9

HUMAN PRESCRIPTION DRUG LABEL

Dec 12, 2023

A-S Medication Solutions

DUNS: 830016429

Products 2

Detailed information about drug products covered under this FDA approval, including NDC codes, dosage forms, ingredients, and administration routes.

Quetiapine Fumarate

Product Details

FDA regulatory identification and product classification information

FDA Identifiers

Product Classification

Product Specifications

INGREDIENTS (10)

Quetiapine Fumarate

Product Details

FDA regulatory identification and product classification information

FDA Identifiers

Product Classification

Product Specifications

INGREDIENTS (12)

Drug Labeling Information

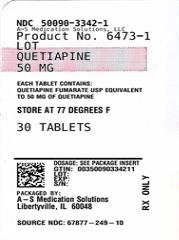

PACKAGE LABEL.PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL

Quetiapine Fumarate

Indications & Usage Section

1 INDICATIONS & USAGE

1.1 Schizophrenia

Quetiapine is indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia. The efficacy of quetiapine in schizophrenia was established in three 6-week trials in adults and one 6-week trial in adolescents (13 to 17 years). The effectiveness of quetiapine for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia has not been systematically evaluated in controlled clinical trials [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

1.2 Bipolar Disorder

Quetiapine is indicated for the acute treatment of manic episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, both as monotherapy and as an adjunct to lithium or divalproex. Efficacy was established in two 12-week monotherapy trials in adults, in one 3-week adjunctive trial in adults, and in one 3-week monotherapy trial in pediatric patients (10 to 17 years) [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Quetiapine is indicated as monotherapy for the acute treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder. Efficacy was established in two 8-week monotherapy trials in adult patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorder [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

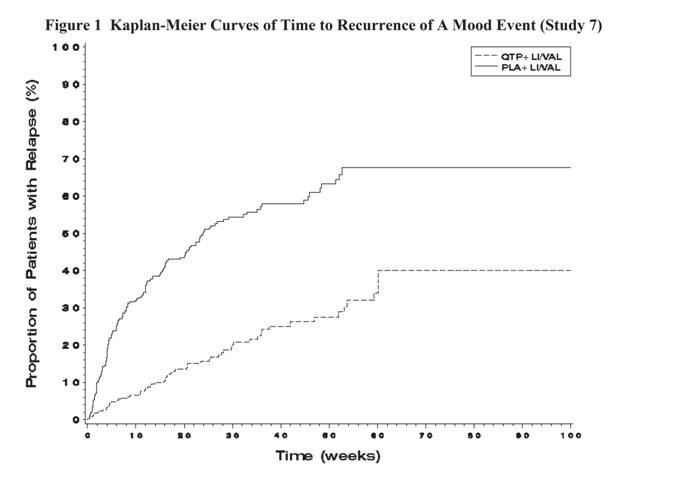

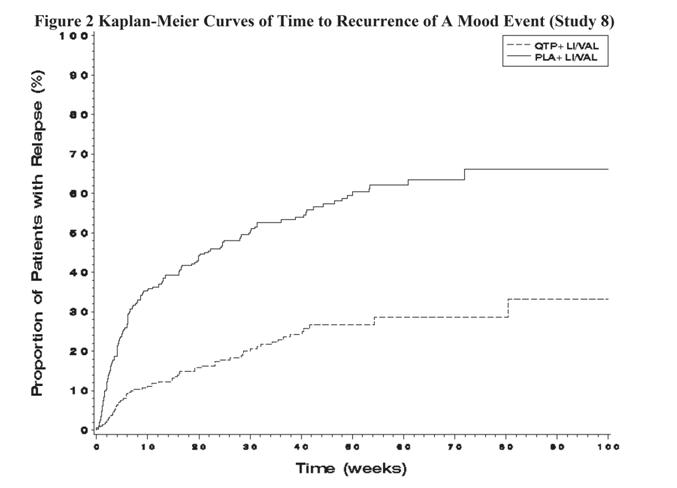

Quetiapine is indicated for the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder, as an adjunct to lithium or divalproex. Efficacy was established in two maintenance trials in adults. The effectiveness of quetiapine as monotherapy for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder has not been systematically evaluated in controlled clinical trials [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

1.3 Special Considerations in Treating Pediatric Schizophrenia and Bipolar

I Disorder

Pediatric schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder are serious mental disorders, however, diagnosis can be challenging. For pediatric schizophrenia, symptom profiles can be variable, and for bipolar I disorder, patients may have variable patterns of periodicity of manic or mixed symptoms. It is recommended that medication therapy for pediatric schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder be initiated only after a thorough diagnostic evaluation has been performed and careful consideration given to the risks associated with medication treatment. Medication treatment for both pediatric schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder is indicated as part of a total treatment program that often includes psychological, educational and social interventions.

Warnings And Precautions Section

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analysis of 17 placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug- treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. quetiapine is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia- related psychosis [see Boxed Warning].

5.2 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Adolescents and Young Adults

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications, and this risk may persist until significant remission occurs. Suicide is a known risk of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, and these disorders themselves are the strongest predictors of suicide. There has been a long-standing concern, however, that antidepressants may have a role in inducing worsening of depression and the emergence of suicidality in certain patients during the early phases of treatment. Pooled analyses of short-term placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and others) showed that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18 to 24) with major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older.

The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with MDD, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 24 short-term trials of 9 antidepressant drugs in over 4400 patients. The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in adults with MDD or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 295 short-term trials (median duration of 2 months) of 11 antidepressant drugs in over 77,000 patients. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidality among drugs, but a tendency toward an increase in the younger patients for almost all drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidality across the different indications, with the highest incidence in MDD. The risk differences (drug vs. placebo), however, were relatively stable within age strata and across indications. These risk differences (drug-placebo difference in the number of cases of suicidality per 1000 patients treated) are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Cases of Suicidality per 1000 Patients Treated

|

Age Range |

Drug - Placebo Difference in |

|

Increases Compared to Placebo | |

|

<18 |

14 additional cases |

|

18 to 24 |

5 additional cases |

|

Decreases Compared to Placebo | |

|

25 to 64 |

1 fewer case |

|

≥65 |

6 fewer cases |

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

It is unknown whether the suicidality risk extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond several months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo- controlled maintenance trials in adults with depression that the use of antidepressants can delay the recurrence of depression.

All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.

The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric. Although a causal link between the emergence of such symptoms and either the worsening of depression and/or the emergence of suicidal impulses has not been established, there is concern that such symptoms may represent precursors to emerging suicidality.

Consideration should be given to changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing the medication, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidality or symptoms that might be precursors to worsening depression or suicidality, especially if these symptoms are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient's presenting symptoms.

**Families and caregivers of patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder or other indications, both psychiatric and non- psychiatric, should be alerted about the need to monitor patients for the emergence of agitation, irritability, unusual changes in behavior, and the other symptoms described above, as well as the emergence of suicidality, and to report such symptoms immediately to healthcare providers. Such monitoring should include daily observation by families and caregivers.**Prescriptions for quetiapine should be written for the smallest quantity of tablets consistent with good patient management, in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

**Screening Patients for Bipolar Disorder:**A major depressive episode may be the initial presentation of bipolar disorder. It is generally believed (though not established in controlled trials) that treating such an episode with an antidepressant alone may increase the likelihood of precipitation of a mixed/manic episode in patients at risk for bipolar disorder. Whether any of the symptoms described above represent such a conversion is unknown. However, prior to initiating treatment with an antidepressant, including quetiapine, patients with depressive symptoms should be adequately screened to determine if they are at risk for bipolar disorder; such screening should include a detailed psychiatric history, including a family history of suicide, bipolar disorder, and depression.

5.3 Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke, in Elderly

Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis

In placebo-controlled trials with risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine in elderly subjects with dementia, there was a higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions (cerebrovascular accidents and transient ischemic attacks) including fatalities compared to placebo-treated subjects. Quetiapine is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia- related psychosis [see also Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

5.4 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome(NMS)

A potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with administration of antipsychotic drugs, including quetiapine. Rare cases of NMS have been reported with quetiapine. Clinical manifestations of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia). Additional signs may include elevated creatinine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis) and acute renal failure.

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with this syndrome is complicated. In arriving at a diagnosis, it is important to exclude cases where the clinical presentation includes both serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection, etc.) and untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal signs and symptoms (EPS). Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, drug fever, and primary central nervous system (CNS) pathology.

The management of NMS should include: 1) immediate discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs and other drugs not essential to concurrent therapy; 2) intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and 3) treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems for which specific treatments are available. There is no general agreement about specific pharmacological treatment regimens for NMS.

If a patient requires antipsychotic drug treatment after recovery from NMS, the potential reintroduction of drug therapy should be carefully considered. The patient should be carefully monitored since recurrences of NMS have been reported.

5.5 Metabolic Changes

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that include hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and body weight gain. While all of the drugs in the class have been shown to produce some metabolic changes, each drug has its own specific risk profile. In some patients, a worsening of more than one of the metabolic parameters of weight, blood glucose, and lipids was observed in clinical studies. Changes in these metabolic profiles should be managed as clinically appropriate.

Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemia, in some cases extreme and associated with ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma or death, has been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics, including quetiapine. Assessment of the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and glucose abnormalities is complicated by the possibility of an increased background risk of diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia and the increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus in the general population. Given these confounders, the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and hyperglycemia-related adverse reactions is not completely understood. However, epidemiological studies suggest an increased risk of hyperglycemia-related adverse reactions in patients treated with the atypical antipsychotics. Precise risk estimates for hyperglycemia-related adverse reactions in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics are not available.

Patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. Patients with risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes) who are starting treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing at the beginning of treatment and periodically during treatment. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia during treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of anti-diabetic treatment despite discontinuation of the suspect drug.

Adults:

Table 3: Fasting Glucose – Proportion of Patients Shifting to ≥ 126 mg/dL in Short-Term (≤12 weeks) Placebo-Controlled Studies1

|

Laboratory Analyte |

Category Change ( At Least Once) from Baseline |

Treatment Arm |

N |

Patients |

|

Fasting Glucose |

Normal to High (<100 mg /dL to ≥126 mg/dL/) |

Quetiapine |

2907 |

71 (2.4%) |

|

Placebo |

1346 |

19 (1.4%) | ||

|

Borderline to High (≥ 100 mg/dL) and <126 mg /dL to ≥126 mg/dL) |

Quetiapine |

572 |

67 (11.7%) | |

|

Placebo |

279 |

33 (11.8%) |

1. Includes quetiapine tablets and SEROQUEL XR data.

In a 24-week trial (active-controlled, 115 patients treated with quetiapine) designed to evaluate glycemic status with oral glucose tolerance testing of all patients, at week 24 the incidence of a post-glucose challenge glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL was 1.7% and the incidence of a fasting blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dL was 2.6%. The mean change in fasting glucose from baseline was 3.2 mg/dL and mean change in 2-hour glucose from baseline was -1.8 mg/dL for quetiapine.

In 2 long-term placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal clinical trials for bipolar I disorder maintenance, mean exposure of 213 days for quetiapine (646 patients) and 152 days for placebo (680 patients), the mean change in glucose from baseline was +5.0 mg/dL for quetiapine and –0.05 mg/dL for placebo. The exposure-adjusted rate of any increased blood glucose level (≥ 126 mg/dL) for patients more than 8 hours since a meal (however, some patients may not have been precluded from calorie intake from fluids during fasting period) was 18.0 per 100 patient years for quetiapine (10.7% of patients; n=556) and 9.5 for placebo per 100 patient years (4.6% of patients; n=581).

Children and Adolescents:

In a placebo-controlled quetiapine monotherapy study of adolescent patients (13 to 17 years of age) with schizophrenia (6 weeks duration), the mean change in fasting glucose levels for quetiapine (n=138) compared to placebo (n=67) was – 0.75 mg/dL versus –1.70 mg/dL. In a placebo-controlled quetiapine monotherapy study of children and adolescent patients (10–17 years of age) with bipolar mania (3 weeks duration), the mean change in fasting glucose level for quetiapine (n=170) compared to placebo (n=81) was 3.62 mg/dL versus –1.17 mg/dL. No patient in either study with a baseline normal fasting glucose level (<100 mg/dL) or a baseline borderline fasting glucose level (≥ 100 mg/dL and <126mg/dL) had a blood glucose level of ≥ 126mg/dL.

In a placebo-controlled SEROQUEL XR monotherapy study (8 weeks duration) of children and adolescent patients (10 to 17 years of age) with bipolar depression, in which efficacy was not established, the mean change in fasting glucose levels for SEROQUEL XR (n = 60) compared to placebo (n = 62) was 1.8 mg/dL versus 1.6 mg/dL. In this study, there were no patients in the SEROQUEL XR or placebo-treated groups with a baseline normal fasting glucose level (< 100 mg/dL) that had an increase in blood glucose level > 126 mg/dL. There was one patient in the SEROQUEL XR group with a baseline borderline fasting glucose level (> 100 mg/dL) and (< 126 mg/dL) who had an increase in blood glucose level of > 126 mg/dL compared to zero patients in the placebo group.

Dyslipidemia

Adults:

Table 4 shows the percentage of adult patients with changes in total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol and HDL- cholesterol from baseline by indication in clinical trials with Quetiapine.

Table 4: Percentage of Adult Patients with Shifts in Total Cholesterol, Triglycerides, LDL-Cholesterol and HDL-Cholesterol from Baseline to Clinically Significant Levels by Indication

|

Laboratory Analyte |

Indication |

Treatment Arm |

N |

Patients |

|

Total Cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

137 |

24 (18 %) |

|

Placebo |

92 |

6 (7%) | ||

|

Bipolar Depression2 |

Quetiapine |

463 |

41 (9 %) | |

|

Placebo |

250 |

15 (6%) | ||

|

Triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

120 |

26 (22 %) |

|

Placebo |

70 |

11 (16 %) | ||

|

Bipolar Depression2 |

Quetiapine |

436 |

59 (14 %) | |

|

Placebo |

232 |

20 (9%) | ||

|

LDL-Cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

na3 |

na3 |

|

Placebo |

na3 |

na3 | ||

|

Bipolar Depression2 |

Quetiapine |

465 |

29 (6 %) | |

|

Placebo |

256 |

12 (5%) | ||

|

HDL-Cholesterol ≤ 40 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

na3 |

na3 |

|

Placebo |

na3 |

na3 | ||

|

Bipolar Depression2 |

Quetiapine |

393 |

56 (14 %) | |

|

Placebo |

214 |

29 (14 %) |

1. 6 weeks duration

2. 8 weeks duration

3. Parameters not measured in the quetiapine registration studies for

schizophrenia.

Children and Adolescents:

Table 5 shows the percentage of children and adolescents with changes in total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol from baseline in clinical trials with quetiapine.

Table 5: Percentage of Children and Adolescents with Shifts in Total Cholesterol, Triglycerides, LDL- Cholesterol and HDL-Cholesterol from Baseline to Clinically Significant Levels

|

Laboratory Analyte |

Indication |

Treatment Arm |

N |

Patients |

|

Total Cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

107 |

13 (12%) |

|

Placebo |

56 |

1 (2%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania2 |

Quetiapine |

159 |

16 (10%) | |

|

Placebo |

66 |

2 (3%) | ||

|

Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

103 |

17 (17%) |

|

Placebo |

51 |

4 (8%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania2 |

Quetiapine |

149 |

32 (22%) | |

|

Placebo |

60 |

8 (13%) | ||

|

LDL-Cholesterol ≥ 130 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

112 |

4 (4%) |

|

Placebo |

60 |

1 (2%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania2 |

Quetiapine |

169 |

13 (8%) | |

|

Placebo |

74 |

4 (5%) | ||

|

HDL-Cholesterol ≤ 40 mg/dL |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

104 |

16 (15%) |

|

Placebo |

54 |

10 (19%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania2 |

Quetiapine |

154 |

16 (10%) | |

|

Placebo |

61 |

4 (7%) |

1. 13 to 17 years, 6 weeks duration

2. 10 to 17 years, 3 weeks duration

In a placebo-controlled SEROQUEL XR monotherapy study (8 weeks duration) of children and adolescent patients (10 to 17 years of age) with bipolar depression, in which efficacy was not established, the percentage of children and adolescents with shifts in total cholesterol (≥200 mg/dL), triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL), LDL-cholesterol (≥130 mg/dL) and HDL-cholesterol (≤ 40 mg/dL) from baseline to clinically significant levels were: total cholesterol 8% (7/83) for SEROQUEL XR vs. 6% (5/84) for placebo; triglycerides 28% (22/80) for SEROQUEL XR vs. 9% (7/82) for placebo; LDL-cholesterol 2% (2/86) for SEROQUEL XR vs. 4% (3/85) for placebo and HDL-cholesterol 20% (13/65) for SEROQUEL XR vs. 15% (11/74) for placebo.

Weight Gain

Increases in weight have been observed in clinical trials. Patients receiving quetiapine should receive regular monitoring of weight.

Adults:

In clinical trials with quetiapine the following increases in weight have been reported.

Table 6:Proportion of Patients with Weight Gain ≥ 7% of Body Weight (Adults)

|

Vital |

Indication |

Treatment Arm |

N |

Patients |

|

Weight Gain ≥7 % of Body Weight |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

391 |

89 (23%) |

|

Placebo |

206 |

11 (6%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania ( monotherapy)2 |

Quetiapine |

209 |

44 (21%) | |

|

Placebo |

198 |

13 (7%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania (adjunct therapy)3 |

Quetiapine |

196 |

25 (13%) | |

|

Placebo |

203 |

8 (4%) | ||

|

Bipolar Depression4 |

Quetiapine |

554 |

47 (8%) | |

|

Placebo |

295 |

7 (2%) |

1. up to 6 weeks duration

2. up to 12 weeks duration

3. up to 3 weeks duration

4. up to 8 weeks duration

Children and Adolescents:

In two clinical trials with quetiapine, one in bipolar mania and one in schizophrenia, reported increases in weight are included in Table 7.

** Table 7: Proportion of Patients with Weight Gain ≥ 7% of Body Weight (Children and Adolescents)**

|

Vital |

Indication |

Treatment Arm |

N |

Patients |

|

Weight Gain ≥7 % of Body |

Schizophrenia1 |

Quetiapine |

111 |

23 (21%) |

|

Placebo |

44 |

3 (7%) | ||

|

Bipolar Mania2 |

Quetiapine |

157 |

18 (12%) | |

|

Placebo |

68 |

0 (0%) |

1. 6 weeks duration

2. 3 weeks duration

The mean change in body weight in the schizophrenia trial was 2.0 kg in the quetiapine group and -0.4 kg in the placebo group and in the bipolar mania trial, it was 1.7 kg in the quetiapine group and 0.4 kg in the placebo group.

In an open-label study that enrolled patients from the above two pediatric trials, 63% of patients (241/380) completed 26 weeks of therapy with quetiapine. After 26 weeks of treatment, the mean increase in body weight was 4.4 kg. Forty-five percent of the patients gained ≥ 7% of their body weight, not adjusted for normal growth. In order to adjust for normal growth over 26 weeks, an increase of at least 0.5 standard deviation from baseline in BMI was used as a measure of a clinically significant change; 18.3% of patients on quetiapine met this criterion after 26 weeks of treatment.

In a clinical trials for SEROQUEL XR in children and adolescents (10 to 17 years of age) with bipolar depression, in which efficacy was not established, the percentage of patients with weight gain ≥ 7% of body weight at any time was 15% (14/92) for SEROQUEL XR vs. 10% (10/100) for placebo. The mean change in body weight was 1.4 kg in the SEROQUEL XR group vs. 0.6 kg in the placeo group.

When treating pediatric patients with quetiapine for any indication, weight gain should be assessed against that expected for normal growth.

5.6 Tardive Dyskinesia

A syndrome of potentially irreversible, involuntary, dyskinetic movements may develop in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs, including quetiapine. Although the prevalence of the syndrome appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women, it is impossible to rely upon prevalence estimates to predict, at the inception of antipsychotic treatment, which patients are likely to develop the syndrome. Whether antipsychotic drug products differ in their potential to cause tardive dyskinesia is unknown.

The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and the likelihood that it will become irreversible are believed to increase as the duration of treatment and the total cumulative dose of antipsychotic drugs administered to the patient increase. However, the syndrome can develop, although much less commonly, after relatively brief treatment periods at low doses or may even arise after discontinuation of treatment.

Tardive dyskinesia may remit, partially or completely, if antipsychotic treatment is withdrawn. Antipsychotic treatment, itself, however, may suppress (or partially suppress) the signs and symptoms of the syndrome and thereby may possibly mask the underlying process. The effect that symptomatic suppression has upon the long-term course of the syndrome is unknown.

Given these considerations, quetiapine should be prescribed in a manner that is most likely to minimize the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. Chronic antipsychotic treatment should generally be reserved for patients who appear to suffer from a chronic illness that (1) is known to respond to antipsychotic drugs, and (2) for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate. In patients who do require chronic treatment, the smallest dose and the shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response should be sought. The need for continued treatment should be reassessed periodically.

If signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear in a patient on quetiapine, drug discontinuation should be considered. However, some patients may require treatment with quetiapine despite the presence of the syndrome.

5.7 Hypotension

Quetiapine may induce orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness, tachycardia and, in some patients, syncope, especially during the initial dose-titration period, probably reflecting its α1 -adrenergic antagonist properties. Syncope was reported in 1% (28/3265) of the patients treated with quetiapine, compared with 0.2% (2/954) on placebo and about 0.4% (2/527) on active control drugs. Orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, and syncope may lead to falls.

Quetiapine should be used with particular caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or conduction abnormalities), cerebrovascular disease or conditions which would predispose patients to hypotension (dehydration, hypovolemia, and treatment with antihypertensive medications). The risk of orthostatic hypotension and syncope may be minimized by limiting the initial dose to 25 mg twice daily [see Dosage and Administration (2.2)]. If hypotension occurs during titration to the target dose, a return to the previous dose in the titration schedule is appropriate.

5.8 Falls

Atypical antipsychotic drugs, including quetiapine, may cause somnolence, postural hypotension, motor, and sensory instability, which may lead to falls and, consequently, fractures or other injuries. For patients with diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate these effects, complete fall risk assessments when initiating antipsychotic treatment and recurrently for patients on long-term antipsychotic therapy.

5.9 Increases in Blood Pressure(Children and Adolescents)

In placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with schizophrenia (6-week duration) or bipolar mania (3-week duration), the incidence of increases at any time in systolic blood pressure (≥20 mm Hg) was 15.2% (51/335) for quetiapine and 5.5% (9./163) for placebo; the incidence of increases at any time in diastolic blood pressure (≥10 mmHg) was 40.6% (136/335) for quetiapine and 24.5% (40/163) for placebo. In the 26-week open- label clinical trial, one child with a reported history of hypertension experienced a hypertensive crisis. Blood pressure in children and adolescents should be measured at the beginning of, and periodically during treatment.

In a placebo-controlled SEROQUEL XR clinical trial (8 weeks duration) in children and adolescents (10 to 17 years of age) with bipolar depression, in which efficacy was not established, the incidence of increases at any time in systolic blood pressure (≥ 20 mmHg) was 6.5% (6/92) for SEROQUEL XR and 6.0% (6/100) for placebo; the incidence of increases at any time in diastolic blood pressure (≥ 10 mmHg) was 46.7% (43/92) for SEROQUEL XR and 36.0% (36/100) for placebo.

5.10 Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

In clinical trial and postmarketing experience, events of leukopenia/neutropenia have been reported temporally related to atypical antipsychotic agents, including quetiapine. Agranulocytosis has been reported.

Agranulocytosis (defined as absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3) has been reported with quetiapine, including fatal cases and cases in patients without pre-existing risk factors. Neutropenia should be considered in patients presenting with infection, particularly in the absence of obvious predisposing factor(s), or in patients with unexplained fever, and should be managed as clinically appropriate.

Possible risk factors for leukopenia/neutropenia include pre-existing low white cell count (WBC) and history of drug induced leukopenia/neutropenia. Patients with a pre-existing low WBC or a history of drug induced leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and should discontinue quetiapine at the first sign of a decline in WBC in absence of other causative factors.

Patients with neutropenia should be carefully monitored for fever or other symptoms or signs of infection and treated promptly if such symptoms or signs occur. Patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1000/mm3) should discontinue quetiapine and have their WBC followed until recovery.

5.11 Cataracts

The development of cataracts was observed in association with quetiapine treatment in chronic dog studies [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.2)]. Lens changes have also been observed in adults, children, and adolescents during long- term quetiapine treatment, but a causal relationship to quetiapine use has not been established. Nevertheless, the possibility of lenticular changes cannot be excluded at this time. Therefore, examination of the lens by methods adequate to detect cataract formation, such as slit lamp exam or other appropriately sensitive methods, is recommended at initiation of treatment or shortly thereafter, and at 6-month intervals during chronic treatment.

5.12 QT Prolongation

In clinical trials, quetiapine was not associated with a persistent increase in QT intervals. However, the QT effect was not systematically evaluated in a thorough QT study. In post marketing experience, there were cases reported of QT prolongation in patients who overdosed on quetiapine [see Overdosage (10.1)], in patients with concomitant illness, and in patients taking medicines known to cause electrolyte imbalance or increase QT interval [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

The use of quetiapine should be avoided in combination with other drugs that are known to prolong QTc including Class 1A antiarrythmics (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) or Class III antiarrythmics (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol), antipsychotic medications (e.g., ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, thioridazine), antibiotics (e.g., gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin), or any other class of medications known to prolong the QTc interval (e.g., pentamidine, levomethadyl acetate, methadone).

Quetiapine should also be avoided in circumstances that may increase the risk of occurrence of torsade de pointes and/or sudden death including (1) a history of cardiac arrhythmias such as bradycardia; (2) hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia; (3) concomitant use of other drugs that prolong the QTc interval; and (4) presence of congenital prolongation of the QT interval.

Caution should also be exercised when quetiapine is prescribed in patients with increased risk of QT prolongation (e.g., cardiovascular disease, family history of QT prolongation, the elderly, congestive heart failure and heart hypertrophy).

5.13 Seizures

During clinical trials, seizures occurred in 0.5% (20/3490) of patients treated with quetiapine compared to 0.2% (2/954) on placebo and 0.7% (4/527) on active control drugs. As with other antipsychotics, quetiapine should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that potentially lower the seizure threshold, e.g., Alzheimer’s dementia. Conditions that lower the seizure threshold may be more prevalent in a population of 65 years or older.

5.14 Hypothyroidism

Adults: Clinical trials with quetiapine demonstrated dose-related decreases in thyroid hormone levels. The reduction in total and free thyroxine (T4) of approximately 20% at the higher end of the therapeutic dose range was maximal in the first six weeks of treatment and maintained without adaptation or progression during more chronic therapy. In nearly all cases, cessation of quetiapine treatment was associated with a reversal of the effects on total and free T4, irrespective of the duration of treatment. The mechanism by which quetiapine effects the thyroid axis is unclear. If there is an effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, measurement of TSH alone may not accurately reflect a patient’s thyroid status. Therefore, both TSH and free T4, in addition to clinical assessment, should be measured at baseline and at follow- up.

In the mania adjunct studies, where quetiapine was added to lithium or divalproex, 12% (24/196) of quetiapine treated patients compared to 7% (15/203) of placebo-treated patients had elevated TSH levels. Of the quetiapine treated patients with elevated TSH levels, 3 had simultaneous low free T4 levels (free T4 <0.8 LLN).

About 0.7% (26/3489) of quetiapine patients did experience TSH increases in monotherapy studies. Some patients with TSH increases needed replacement thyroid treatment.

In all quetiapine trials, the incidence of shifts in thyroid hormones and TSH were1: decrease in free T4 (<0.8 LLN), 2.0% (357/17513); decrease in total T4 (<0.8 LLN), 4.0% (75/1861); decrease in free T3 (<0.8 LLN), 0.4% (53/13766); decrease in total T3 (<0.8 LLN), 2.0% (26/1312), and increase in TSH (>5mIU/L), 4.9% (956/19412). In eight patients, where TBG was measured, levels of TBG were unchanged.

Table 8 shows the incidence of these shifts in short term placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Table 8: Incidence of Shifts in Thyroid Hormone Levels and TSH in Short-Term Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials****1,2

|

Total T**4** |

Free T**4** |

Total T**3** |

Free T**3** |

TSH | |||||

|

Quetiapine |

Placebo |

Quetiapine |

Placebo |

Quetiapine |

Placebo |

Quetiapine |

Placebo |

Quetiapine |

Placebo |

|

3.4 % |

0.6% |

0.7% |

0.1% |

0. 5% |

0. 0% |

0. 2% |

0. 0% |

3. 2% |

2. 7% (105/3912) |

1. Based on shifts from normal baseline to potentially clinically important

value at anytime post-baseline. Shifts in total T4, free T4, total T3 and free

T3 are defined as <0.8 x LLN (pmol/L) and shift in TSH is >5 mlU/L at any

time.

2. Includes quetiapine and SEROQUEL XR data

In short-term placebo-controlled monotherapy trials, the incidence of reciprocal, shifts in T3 and TSH was 0.0 % for both quetiapine (1/4800) and placebo (0/2190) and for T4 and TSH the shifts were 0.1% (7/6154) for quetiapine versus 0.0% (1/3007) for placebo.

Children and Adolescents:

In acute placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescent patients with schizophrenia (6-week duration) or bipolar mania (3-week duration), the incidence of shifts for thyroid function values at any time for Quetiapine treated patients and placebo-treated patients for elevated TSH was 2.9% (8/280) vs. 0.7% (1/138), respectively, and for decreased total thyroxine was 2.8% (8/289) vs. 0% (0/145), respectively. Of the Quetiapine treated patients with elevated TSH levels, 1 had simultaneous low free T4 level at end of treatment.

5.15 Hyperprolactinemia

Adults: During clinical trials with quetiapine, the incidence of shifts in prolactin levels to a clinically significant value occurred in 3.6% (158/4416) of patients treated with quetiapine compared to 2.6% (51/1968) on placebo.

Children and Adolescents:

In acute placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescent patients with bipolar mania (3-week duration) or schizophrenia (6-week duration), the incidence of shifts in prolactin levels to a value (>20 μg/L males; > 26 μg/L females at any time) was 13.4% (18/134) for quetiapine compared to 4% (3/75) for placebo in males and 8.7% (9/104) for quetiapine compared to 0% (0/39) for placebo in females.

Like other drugs that antagonize dopamine D2 receptors, quetiapine elevates prolactin levels in some patients and the elevation may persist during chronic administration. Hyperprolactinemia, regardless of etiology, may suppress hypothalamic GnRH, resulting in reduced pituitary gonadotrophin secretion. This, in turn, may inhibit reproductive function by impairing gonadal steroidogenesis in both female and male patients. Galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and impotence have been reported in patients receiving prolactin-elevating compounds. Long-standing hyperprolactinemia when associated with hypogonadism may lead to decreased bone density in both female and male subjects.

Tissue culture experiments indicate that approximately one-third of human breast cancers are prolactin dependent in vitro, a factor of potential importance if the prescription of these drugs is considered in a patient with previously detected breast cancer. As is common with compounds which increase prolactin release, mammary gland, and pancreatic islet cell neoplasia (mammary adenocarcinomas, pituitary, and pancreatic adenomas) was observed in carcinogenicity studies conducted in mice and rats. Neither clinical studies nor epidemiologic studies conducted to date have shown an association between chronic administration of this class of drugs and tumorigenesis in humans, but the available evidence is too limited to be conclusive [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)].

5.16 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

Somnolence was a commonly reported adverse event reported in patients treated with quetiapine especially during the 3-5 day period of initial dose- titration. In schizophrenia trials, somnolence was reported in 18% (89/510) of patients on quetiapine compared to 11% (22/206) of placebo patients. In acute bipolar mania trials using quetiapine as monotherapy, somnolence was reported in 16% (34/209) of patients on quetiapine compared to 4% of placebo patients. In acute bipolar mania trials using quetiapine as adjunct therapy, somnolence was reported in 34% (66/196) of patients on quetiapine compared to 9% (19/203) of placebo patients. In bipolar depression trials, somnolence was reported in 57% (398/698) of patients on quetiapine compared to 15% (51/347) of placebo patients. Since quetiapine has the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, patients should be cautioned about performing activities requiring mental alertness, such as operating a motor vehicle (including automobiles) or operating hazardous machinery until they are reasonably certain that quetiapine therapy does not affect them adversely. Somnolence may lead to falls.

5.17 Body Temperature Regulation

Although not reported with quetiapine, disruption of the body's ability to reduce core body temperature has been attributed to antipsychotic agents. Appropriate care is advised when prescribing quetiapine for patients who will be experiencing conditions which may contribute to an elevation in core body temperature, e.g., exercising strenuously, exposure to extreme heat, receiving concomitant medication with anticholinergic activity, or being subject to dehydration.

5.18 Dysphagia

Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with antipsychotic drug use. Aspiration pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in elderly patients, in particular those with advanced Alzheimer's dementia. Quetiapine and other antipsychotic drugs should be used cautiously in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia.

5.19 Discontinuation Syndrome

Acute withdrawal symptoms, such as insomnia, nausea, and vomiting have been described after abrupt cessation of atypical antipsychotic drugs, including quetiapine.

In short-term placebo-controlled, monotherapy clinical trials with SEROQUEL XR that included a discontinuation phase which evaluated discontinuation symptoms, the aggregated incidence of patients experiencing one or more discontinuation symptoms after abrupt cessation was 12.1% (241/1993) for SEROQUEL XR and 6.7% (71/1065) for placebo.

The incidence of the individual adverse reactions (i.e., insomnia, nausea, headache, diarrhea, vomiting, dizziness, and irritability) did not exceed 5.3% in any treatment group and usually resolved after 1 week post-discontinuation. Gradual withdrawal is advised. [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)]

5.20 Anticholinergic (antimuscarinic) Effects

Norquetiapine, an active metabolite of quetiapine, has moderate to strong affinity for several muscarinic receptor subtypes. This contributes to anticholinergic adverse reactions when quetiapine is used at therapeutic doses, taken concomitantly with other anticholinergic medications, or taken in overdose. Quetiapine should be used with caution in patients receiving medications having anticholinergic (antimuscarinic) effects [see Drug Interactions (7.1), Overdosage (10.1), and Clinical Pharmacology (12.1)].

Constipation was a commonly reported adverse event in patients treated with quetiapine and represents a risk factor for intestinal obstruction. Intestinal obstruction has been reported with quetiapine, including fatal reports in patients who were receiving multiple concomitant medications that decrease intestinal motility.

Quetiapine tablets should be used with caution in patients with a current diagnosis or prior history of urinary retention, clinically significant prostatic hypertrophy, or constipation.

· Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions: Increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack) has been seen in elderly patients with dementia-related psychoses treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs (5.3)

· Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS): Manage with immediate discontinuation and close monitoring (5.4)

· Metabolic Changes: Atypical antipsychotics have been associated with metabolic changes.

These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and weight gain (5.5)

· Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus: Monitor patients for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Monitor glucose regularly in patients with diabetes or at risk for diabetes

· Dyslipidemia: Undesirable alterations have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Appropriate clinical monitoring is recommended, including fasting blood lipid testing at the beginning of, and periodically, during treatment

· Weight Gain: Gain in body weight has been observed; clinical monitoring of weight is recommended

· Tardive Dyskinesia: Discontinue if clinically appropriate (5.6)

· Hypotension: Use with caution in patients with known cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease (5.7)

· Increased Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: Monitor blood pressure at the beginning of, and periodically during treatment in children and adolescents (5.9)

· Leukopenia, Neutropenia and Agranulocytosis: Monitor complete blood count frequently during the first few months of treatment in patients with a pre- existing low white cell count or a history of leukopenia/neutropenia and discontinue quetiapine at the first sign of a decline in WBC in absence of other causative factors (5.10)

· Cataracts: Lens changes have been observed in patients during long-term quetiapine treatment. Lens examination is recommended when starting treatment and at 6-month intervals during chronic treatment (5.11)

· Anticholinergic (antimuscarinic) Effects: Use with caution with other anticholinergic drugs and in patients with urinary retention, prostatic hypertrophy, or constipation (5.20)

Dosage & Administration Section

2 DOSAGE & ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Important Administration Instructions

Quetiapine tablets, USP can be taken with or without food.

2.2 Recommended Dosing

The recommended initial dose, titration, dose range and maximum quetiapine dose for each approved indication is displayed in Table 1. After initial dosing, adjustments can be made upwards or downwards, if necessary, depending upon the clinical response and tolerability of the patient [see Clinical Studies (14.1 and 14.2)].

Table 1: Recommended Dosing for quetiapine

|

Indication |

Initial Dose and Titration |

Recommended Dose |

Maximum Dose |

|

Schizophrenia-Adults |

Day 1: 25 mg twice daily. Increase in increments of 25 mg-50 mg divided two or

three times on Days 2 and 3 to range of 300 to 400 mg by Day 4. |

150 to 750 mg/day |

750 mg/day |

|

Schizophrenia- Adolescents (13 to 17 years) |

Day 1: 25 mg twice daily. |

400 to 800 mg/day |

800 mg/day |

|

Schizophrenia-Maintenance |

Not applicable. |

400 to 800 mg/day |

800 mg/day |

|

Bipolar Mania- Adults Monotherapy or as an adjunct to lithium or divalproex |

Day 1: Twice daily dosing totaling 100 mg. |

400 to 800 mg/day |

800 mg/day |

|

Bipolar Mania- Children and Adolescents (10 to 17 years), |

Day 1: 25 mg twice daily. |

400 to 600 mg/day |

600 mg/day |

|

Bipolar Depression- Adults |

Administer once daily at bedtime. |

300 mg/day |

300 mg/day |

|

Bipolar I Disorder Maintenance Therapy- Adults |

Administer twice daily totaling 400-800 mg/day as adjunct to lithium or divalproex. Generally, in the maintenance phase, patients continued on the same dose on which they were stabilized. |

400 to 800 mg/day |

800 mg/day |

Maintenance Treatment for Schizophrenia and Bipolar I Disorder

** Maintenance Treatment–**Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment and the appropriate dose for such treatment [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

2.3 Dose Modifications in Elderly Patients

Consideration should be given to a slower rate of dose titration and a lower target dose in the elderly and in patients who are debilitated or who have a predisposition to hypotensive reactions [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. When indicated, dose escalation should be performed with caution in these patients.

Elderly patients should be started on quetiapine 50 mg/day and the dose can be increased in increments of 50 mg/day depending on the clinical response and tolerability of the individual patient.

2.4 Dose Modifications in Hepatically Impaired Patients

Patients with hepatic impairment should be started on 25 mg/day. The dose should be increased daily in increments of 25 mg/day - 50 mg/day to an effective dose, depending on the clinical response and tolerability of the patient.

2.5 Dose Modifications when used with CYP3A4 Inhibitors

Quetiapine dose should be reduced to one sixth of original dose when co- medicated with a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor (e.g., ketoconazole, itraconazole, indinavir, ritonavir, nefazodone, etc.). When the CYP3A4 inhibitor is discontinued, the dose of quetiapine should be increased by 6-fold [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

2.6 Dose Modifications when used with CYP3A4 Inducers

Quetiapine dose should be increased up to 5-fold of the original dose when used in combination with a chronic treatment (e.g., greater than 7 to 14 days) of a potent CYP3A4 inducer (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine, rifampin, avasimibe, St. John’s wort etc.). The dose should be titrated based on the clinical response and tolerability of the individual patient. When the CYP3A4 inducer is discontinued, the dose of quetiapine should be reduced to the original level within 7-14 days [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

2.7 Re-initiation of Treatment in Patients Previously Discontinued

Although there are no data to specifically address re-initiation of treatment, it is recommended that when restarting therapy of patients who have been off quetiapine for more than one- week, the initial dosing schedule should be followed. When restarting patients who have been off quetiapine for less than one-week, gradual dose escalation may not be required and the maintenance dose may be re-initiated.

2.8 Switching from Antipsychotics

There are no systematically collected data to specifically address switching patients with schizophrenia from antipsychotics to quetiapine, or concerning concomitant administration with antipsychotics. While immediate discontinuation of the previous antipsychotic treatment may be acceptable for some patients with schizophrenia, more gradual discontinuation may be most appropriate for others. In all cases, the period of overlapping antipsychotic administration should be minimized. When switching patients with schizophrenia from depot antipsychotics, if medically appropriate, initiate quetiapine therapy in place of the next scheduled injection. The need for continuing existing EPS medication should be re-evaluated periodically.

Drug Abuse And Dependence Section

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.1 Controlled Substance

Quetiapine is not a controlled substance.

9.2 Abuse

Quetiapine has not been systematically studied, in animals or humans, for its potential for abuse, tolerance, or physical dependence. While the clinical trials did not reveal any tendency for any drug-seeking behavior, these observations were not systematic and it is not possible to predict on the basis of this limited experience the extent to which a CNS-active drug will be misused, diverted, and/or abused once marketed. Consequently, patients should be evaluated carefully for a history of drug abuse, and such patients should be observed closely for signs of misuse or abuse of quetiapine, e.g., development of tolerance, increases in dose, drug-seeking behavior.

Overdosage Section

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

In clinical trials, survival has been reported in acute overdoses of up to 30 grams of quetiapine. Most patients who overdosed experienced no adverse reactions or recovered fully from the reported reactions. Death has been reported in a clinical trial following an overdose of 13.6 grams of quetiapine alone. In general, reported signs and symptoms were those resulting from an exaggeration of the drug’s known pharmacological effects, i.e., drowsiness, sedation, tachycardia, hypotension, and anticholinergic toxicity including coma and delirium.

Patients with pre-existing severe cardiovascular disease may be at an increased risk of the effects of overdose [see Warnings and Precautions (5.12)]. One case, involving an estimated overdose of 9,600 mg, was associated with hypokalemia and first- degree heart block. In post-marketing experience, there were cases reported of QT prolongation with overdose.

10.2 Management of Overdosage

Establish and maintain an airway and ensure adequate oxygenation and ventilation. Cardiovascular monitoring should commence immediately and should include continuous electrocardiographic monitoring to detect possible arrhythmias.

Appropriate supportive measures are the mainstay of management. For the most up-to-date information on the management of quetiapine overdosage, contact a certified Regional Poison Control Center (1-800-222-1222).

Description Section

11 DESCRIPTION

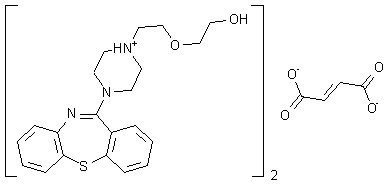

Quetiapine is an atypical antipsychotic belonging to a chemical class, the dibenzothiazepine derivatives. The chemical designation is 2-[2-(4-dibenzo [b,f] [1,4]thiazepin-11-yl-1-piperazinyl) ethoxy]-ethanol fumarate (2:1) (salt). It is present in tablets as the fumarate salt. All doses and tablet strengths are expressed as milligrams of base, not as fumarate salt. Its molecular formula is C42H50N6O4S2•C4H4O4 and it has a molecular weight of 883.11 (fumarate salt). The structural formula is:

Quetiapine fumarate USP is a white to off-white crystalline powder which is moderately soluble in water.

Quetiapine tablets, USP is supplied for oral administration as 25 mg (round peach), 50 mg (round, white), 100 mg (round yellow), 150 mg (round, off white to light yellow), 200 mg (round, white), 300 mg (capsule-shaped, white), and 400 mg (capsule-shaped, yellow) tablets.

Inactive ingredients are povidone, dibasic dicalcium phosphate dihydrate, microcrystalline cellulose, sodium starch glycolate, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, hypromellose, polyethylene glycol and titanium dioxide. The 25 mg tablets contain red iron oxide and yellow iron oxide and the 100 mg, 150 mg and 400 mg tablets contain only yellow iron oxide.

Each 25 mg tablet contains 28.78 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 25 mg quetiapine. Each 50 mg tablet contains 57.56 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 50 mg quetiapine. Each 100 mg tablet contains 115.13 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 100 mg quetiapine. Each 150 mg tablet contains 172.70 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 150 mg quetiapine. Each 200 mg tablet contains 230.27 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 200 mg quetiapine. Each 300 mg tablet contains 345.40 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 300 mg quetiapine. Each 400 mg tablet contains 460.54 mg of quetiapine fumarate USP equivalent to 400 mg quetiapine.

Clinical Pharmacology Section

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of quetiapine in the listed indications is unclear. However, the efficacy of quetiapine in these indications could be mediated through a combination of dopamine type 2 (D2) and serotonin type 2 (5HT2) antagonism. The active metabolite, N-desalkyl quetiapine (norquetiapine), has similar activity at D2, but greater activity at 5HT2A receptors, than the parent drug (quetiapine).

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

Quetiapine and its metabolite, norquetiapine, have affinity for multiple neurotransmitter receptors with norquetiapine binding with higher affinity than quetiapine in general. The Ki values for quetiapine and norquetiapine at the dopamine D1 are 428/99.8 nM, at D2 626/489nM, at serotonin 5HT1A 1040/191 nM at 5HT2A 38/2.9 nM, at histamine H1 4.4/1.1 nM, at muscarinic M1 1086/38.3 nM, and at adrenergic α1b 14.6/46.4 nM and, at α2 receptors 617/1290 nM, respectively. Quetiapine and norquetiapine lack appreciable affinity to the benzodiazepine receptors.

Effect on QT Interval

In clinical trials, quetiapine was not associated with a persistent increase in QT intervals. However, the QT effect was not systematically evaluated in a thorough QT study. In post marketing experience, there were cases reported of QT prolongation in patients who overdosed on quetiapine [see Overdosage (10.1)], in patients with concomitant illness, and in patients taking medicines known to cause electrolyte imbalance or increase QT interval.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Adults

Quetiapine activity is primarily due to the parent drug. The multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of quetiapine are dose-proportional within the proposed clinical dose range, and quetiapine accumulation is predictable upon multiple dosing. Elimination of quetiapine is mainly via hepatic metabolism with a mean terminal half-life of about 6 hours within the proposed clinical dose range. Steady-state concentrations are expected to be achieved within two days of dosing. Quetiapine is unlikely to interfere with the metabolism of drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes.

Children and Adolescents

At steady-state the pharmacokinetics of the parent compound, in children and adolescents (10-17 years of age), were similar to adults. However, when adjusted for dose and weight, AUC and Cmax of the parent compound were 41% and 39% lower, respectively, in children and adolescents than in adults. For the active metabolite, norquetiapine, AUC and Cmax were 45% and 31% higher, respectively, in children and adolescents than in adults. When adjusted for dose and weight, the pharmacokinetics of the metabolite, norquetiapine, was similar between children and adolescents and adults [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

Absorption

Quetiapine is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, reaching peak plasma concentrations in 1.5 hours. The tablet formulation is 100% bioavailable relative to solution. The bioavailability of quetiapine is marginally affected by administration with food, with Cmax and AUC values increased by 25% and 15%, respectively.

Distribution

Quetiapine is widely distributed throughout the body with an apparent volume of distribution of 10±4 L/kg. It is 83% bound to plasma proteins at therapeutic concentrations. In vitro, quetiapine did not affect the binding of warfarin or diazepam to human serum albumin. In turn, neither warfarin nor diazepam altered the binding of quetiapine.

Metabolism and Elimination

Following a single oral dose of 14C-quetiapine, less than 1% of the administered dose was excreted as unchanged drug, indicating that quetiapine is highly metabolized. Approximately 73% and 20% of the dose was recovered in the urine and feces, respectively.

Quetiapine is extensively metabolized by the liver. The major metabolic pathways are sulfoxidation to the sulfoxide metabolite and oxidation to the parent acid metabolite; both metabolites are pharmacologically inactive. In vitro studies using human liver microsomes revealed that the cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme is involved in the metabolism of quetiapine to its major, but inactive, sulfoxide metabolite and in the metabolism of its active metabolite N-desalkyl quetiapine.

Age

Oral clearance of quetiapine was reduced by 40% in elderly patients (≥ 65 years, n=9) compared to young patients (n=12), and dosing adjustment may be necessary [see Dosage and Administration (2.3)].

Gender

There is no gender effect on the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine.

Race

There is no race effect on the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine.

Smoking

Smoking has no effect on the oral clearance of quetiapine.

Renal Insufficiency

Patients with severe renal impairment (Clcr=10-30 mL/min/1.73 m2, n=8) had a 25% lower mean oral clearance than normal subjects (Clcr > 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, n=8), but plasma quetiapine concentrations in the subjects with renal insufficiency were within the range of concentrations seen in normal subjects receiving the same dose. Dosage adjustment is therefore not needed in these patients [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

Hepatic Insufficiency

Hepatically impaired patients (n=8) had a 30% lower mean oral clearance of quetiapine than normal subjects. In two of the 8 hepatically impaired patients, AUC and Cmax were 3 times higher than those observed typically in healthy subjects. Since quetiapine is extensively metabolized by the liver, higher plasma levels are expected in the hepatically impaired population, and dosage adjustment may be needed [see Dosage and Administration (2.4) and Use in Specific Populations (8.7)].

Drug-Drug Interaction Studies

The in vivo assessments of effect of other drugs on the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine are summarized in Table 17 [see Dosage and Administration (2.5 and 2.6) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Table 17: The Effect of Other Drugs on the Pharmacokinetics of Quetiapine

|

Coadministered Drug |

Dose Schedules |

Effect on Quetiapine Pharmacokinetics | |

|

Coadministered Drug |

Quetiapine | ||

|

Phenytoin |

100 mg three times daily |

250 mg three times daily |

5-fold increase in oral clearance |

|

Divalproex |

500 mg twice daily |

150 mg twice daily |

17% increase mean max plasma concentration at steady state. |

|

Thioridazine |

200 mg twice daily |

300 mg twice daily |

65% increase in oral clearance |

|

Cimetidine |

400 mg three times daily for 4 days |

150 mg three times daily |

20% decrease in mean oral clearance |

|

Ketoconazole (potent CYP 3A4 inhibitor) |

200 mg once daily for 4 days |

25 mg single dose |

84% decrease in oral clearance resulting in a 6.2-fold increase in AUC of quetiapine |

|

Fluoxetine |

60 mg once daily |

300 mg twice daily |

No change in steady state PK |

|

Imipramine |

75 mg twice daily |

300 mg twice daily |

No change in steady state PK |

|

Haloperidol |

7.5 mg twice daily |

300 mg twice daily |

No change in steady state PK |

|

Risperidone |

3 mg twice daily |

300 mg twice daily |

No change in steady state PK |

In vitro enzyme inhibition data suggest that quetiapine and 9 of its metabolites would have little inhibitory effect on in vivo metabolism mediated by cytochromes CYP 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4. Quetiapine at doses of 750 mg/day did not affect the single dose pharmacokinetics of antipyrine, lithium, or lorazepam (Table 18) [see Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Table 18: The Effect of Quetiapine on the Pharmacokinetics of Other Drugs

|

Coadministered drug |

Dose schedules |

Effect on other drugs pharmacokinetics | |

|

Coadministered drug |

Quetiapine | ||

|

Lorazepam |

2 mg, single dose |

250 mg three times daily |

Oral clearance of lorazepam reduced by 20% |

|

Divalproex |

500 mg twice daily |

150 mg twice daily |

Cmax and AUC of free valproic acid at steady- state was decreased by 10-12% |

|

Lithium |

Up to 2400 mg/day given in twice daily doses |

250 mg three times daily |

No effect on steady-state pharmacokinetics of lithium |

|

Antipyrine |

1 g, single dose |

250 mg three times daily |

No effect on clearance of antipyrine or urinary recovery of its metabolites |

SPL UNCLASSIFIED SECTION

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Carcinogenicity studies were conducted in C57BL mice and Wistar rats. Quetiapine was administered in the diet to mice at doses of 20, 75, 250, and 750 mg/kg and to rats by gavage at doses of 25, 75, and 250 mg/kg for two years. These doses are equivalent to 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, and 4.5 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area (mice) or 0.3, 1, and 3 times the MRHD based on mg/m2 body surface area (rats). There were statistically significant increases in thyroid gland follicular adenomas in male mice at doses 1.5 and 4.5 times the MRHD based on mg/m2 body surface area and in male rats at a dose of 3 times the MRHD on mg/m2 body surface area. Mammary gland adenocarcinomas were statistically significantly increased in female rats at all doses tested (0.3, 1, and 3 times the MRHD based on mg/m2 body surface area).

Thyroid follicular cell adenomas may have resulted from chronic stimulation of the thyroid gland by thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) resulting from enhanced metabolism and clearance of thyroxine by rodent liver. Changes in TSH, thyroxine, and thyroxine clearance consistent with this mechanism were observed in subchronic toxicity studies in rat and mouse and in a 1-year toxicity study in rat; however, the results of these studies were not definitive. The relevance of the increases in thyroid follicular cell adenomas to human risk, through whatever mechanism, is unknown.

Antipsychotic drugs have been shown to chronically elevate prolactin levels in rodents. Serum measurements in a 1-year toxicity study showed that quetiapine increased median serum prolactin levels a maximum of 32- and 13-fold in male and female rats, respectively. Increases in mammary neoplasms have been found in rodents after chronic administration of other antipsychotic drugs and are considered to be prolactin-mediated. The relevance of this increased incidence of prolactin-mediated mammary gland tumors in rats to human risk is unknown [see Warnings and Precautions (5.15)].

Mutagenesis

Quetiapine was not mutagenic or clastogenic in standard genotoxicity tests. The mutagenic potential of quetiapine was tested in the in vitro Ames bacterial gene mutation assay and in the in vitro mammalian gene mutation assay in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. The clastogenic potential of quetiapine was tested in the in vitro chromosomal aberration assay in cultured human lymphocytes and in the in vivo bone marrow micronucleus assay in rats up to 500 mg/kg, which is 6 times the MRHD based on mg/m2 body surface area.

Impairment of Fertility

Quetiapine decreased mating and fertility in male Sprague-Dawley rats at oral doses of 50 and 150 mg/kg or approximately 1 and 3 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area. Drug- related effects included increases in interval to mate and in the number of matings required for successful impregnation. These effects continued to be observed at 3 times the MRHD even after a two-week period without treatment. The no- effect dose for impaired mating and fertility in male rats was 25 mg/kg, or 0.3 times the MRHD based on mg/m2 body surface area. Quetiapine adversely affected mating and fertility in female Sprague-Dawley rats at an oral dose approximately 1 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area. Drug-related effects included decreases in matings and in matings resulting in pregnancy, and an increase in the interval to mate. An increase in irregular estrus cycles was observed at doses of 10 and 50 mg/kg, or approximately 0.1 and 1 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area. The no-effect dose in female rats was 1 mg/kg, or 0.01 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area.

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

Quetiapine caused a dose-related increase in pigment deposition in thyroid gland in rat toxicity studies which were 4 weeks in duration or longer and in a mouse 2-year carcinogenicity study. Doses were 10, 25, 50, 75, 150 and 250 mg/kg in rat studies which are approximately 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 1, 2 and 3-times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area, respectively. Doses in the mouse carcinogenicity study were 20, 75, 250 and 750 mg/kg which are approximately 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, and 4.5 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area. Pigment deposition was shown to be irreversible in rats. The identity of the pigment could not be determined, but was found to be co-localized with quetiapine in thyroid gland follicular epithelial cells. The functional effects and the relevance of this finding to human risk are unknown.

In dogs receiving quetiapine for 6 or 12 months, but not for 1-month, focal triangular cataracts occurred at the junction of posterior sutures in the outer cortex of the lens at a dose of 100 mg/kg, or 4 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area. This finding may be due to inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis by quetiapine. Quetiapine caused a dose-related reduction in plasma cholesterol levels in repeat-dose dog and monkey studies; however, there was no correlation between plasma cholesterol and the presence of cataracts in individual dogs. The appearance of delta-8- cholestanol in plasma is consistent with inhibition of a late stage in cholesterol biosynthesis in these species. There also was a 25% reduction in cholesterol content of the outer cortex of the lens observed in a special study in quetiapine treated female dogs. Drug-related cataracts have not been seen in any other species; however, in a 1-year study in monkeys, a striated appearance of the anterior lens surface was detected in 2/7 females at a dose of 225 mg/kg or 5.5 times the MRHD of 800 mg/day based on mg/m2 body surface area.

Clinical Studies Section

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Schizophrenia

Short-term Trials-Adults

The efficacy of quetiapine in the treatment of schizophrenia was established in 3 short-term (6-week) controlled trials of inpatients with schizophrenia who met DSM III-R criteria for schizophrenia. Although a single fixed dose haloperidol arm was included as a comparative treatment in one of the three trials, this single haloperidol dose group was inadequate to provide a reliable and valid comparison of quetiapine and haloperidol.

Several instruments were used for assessing psychiatric signs and symptoms in these studies, among them the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), a multi- item inventory of general psychopathology traditionally used to evaluate the effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia. The BPRS psychosis cluster (conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness, and unusual thought content) is considered a particularly useful subset for assessing actively psychotic schizophrenic patients. A second traditional assessment, the Clinical Global Impression (CGI), reflects the impression of a skilled observer, fully familiar with the manifestations of schizophrenia, about the overall clinical state of the patient.

The results of the trials follow:

1. In a 6-week, placebo-controlled trial (n=361) (Study 1) involving 5 fixed doses of quetiapine (75 mg/day, 150 mg/day, 300 mg/day, 600 mg/day and 750 mg/day given in divided doses three times per day), the 4 highest doses of quetiapine were generally superior to placebo on the BPRS total score, the BPRS psychosis cluster and the CGI severity score, with the maximal effect seen at 300 mg/day, and the effects of doses of 150 mg/day to 750 mg/day were generally indistinguishable.

2. In a 6-week, placebo-controlled trial (n=286) (Study 2) involving titration of quetiapine in high (up to 750 mg/day given in divided doses three times per day) and low (up to 250 mg/day given in divided doses three times per day) doses, only the high dose quetiapine group (mean dose, 500 mg/day) was superior to placebo on the BPRS total score, the BPRS psychosis cluster, and the CGI severity score.

3. In a 6-week dose and dose regimen comparison trial (n=618) (Study 3) involving two fixed doses of quetiapine (450 mg/day given in divided doses both twice daily and three times daily and 50 mg/day given in divided doses twice daily), only the 450 mg/day (225 mg given twice daily) dose group was superior to the 50 mg/day (25 mg given twice daily) quetiapine dose group on the BPRS total score, the BPRS psychosis cluster, and the CGI severity score.

The primary efficacy results of these three studies in the treatment of schizophrenia in adults is presented in Table 19. Examination of population subsets (race, gender, and age) did not reveal any differential responsiveness on the basis of race or gender, with an apparently greater effect in patients under the age of 40 years compared to those older than 40. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown.

Adolescents (ages 13 to 17)

The efficacy of quetiapine in the treatment of schizophrenia in adolescents (13 to 17 years of age) was demonstrated in a 6-week, double-blind, placebo- controlled trial (Study 4). Patients who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia were randomized into one of three treatment groups: Quetiapine 400 mg/day (n = 73), Quetiapine 800 mg/day (n = 74), or placebo (n = 75). Study medication was initiated at 50 mg/day and on day 2 increased to 100 mg/per day (divided and given two or three times per day). Subsequently, the dose was titrated to the target dose of 400 mg/day or 800 mg/day using increments of 100 mg/day, divided and given two or three times daily. The primary efficacy variable was the mean change from baseline in total Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Quetiapine at 400 mg/day and 800 mg/day was superior to placebo in the reduction of PANSS total score. The primary efficacy results of this study in the treatment of schizophrenia in adolescents is presented in Table 19.

Table 19: Schizophrenia Short-Term Trials

|

Study |

Treatment Group |

Primary Efficacy Endpoint: BPRS Total | ||

|

Mean Baseline |

LS Mean Change from Baseline (SE) |

Placebo-subtracted Difference1 (95% CI) | ||

|

Study 1 |

Quetiapine (75 mg/day) |

45.7 (10.9) |

-2.2 (2.0) |

-4.0 (-11.2, 3.3) |

|

Quetiapine (150 mg/day)2 |

47.2 (10.1) |

-8.7 (2.1) |

-10.4 (-17.8, -3.0) | |

|

Quetiapine (300 mg/day)2 |

45.3 (10.9) |

-8.6 (2.1) |

-10.3 (-17.6, -3.0) | |

|

Quetiapine (600 mg/day)2 |

43.5 (11.3) |

-7.7 (2.1) |

-9.4 (-16.7, -2.1) | |

|

Quetiapine (750 mg/day)2 |

45.7 (11.0) |

-6.3 (2.0) |

-8.0 (-15.2, -0.8) | |

|

Placebo |

45.3 (9.2) |

1.7 (2.1) |

-- | |

|

Study 2 |

Quetiapine (250 mg/day) |

38.9 (9.8) |

-4.2 (1.6) |

-3.2 (-7.6, 1.2) |

|

Quetiapine (750 mg/day)2 |

41.0 (9.6) |

-8.7 (1.6) |

-7.8 (-12.2, -3.4) | |

|

Placebo |

38.4 (9.7) |

-1.0 (1.6) |

-- | |

|

Study 3 |

Quetiapine (450 mg/day BID) |

42.1 (10.7) |

-10.0 (1.3) |

-4.6 (-7.8, -1.4) |

|

Quetiapine (450 mg/day TID)3 |

42.7 (10.4) |

-8.6 (1.3) |

-3.2 (-6.4, 0.0) | |

|

Quetiapine (50 mg BID) |

41.7 (10.0) |

-5.4 (1.3) |

-- | |

|

Primary Efficacy Endpoint: PANSS Total | ||||

|

Mean Baseline Score (SD) |

LS Mean Change from Baseline (SE) |

Placebo-subtracted Difference1 (95% CI) | ||

|

Study 4 |

Quetiapine (400 mg/day)2 |

96.2 (17.7) |

-27.3 (2.6) |

-8.2 (-16.1, -0.3) |

|

Quetiapine (800 mg/day)2 |

96.9 (15.3) |

-28.4 (1.8) |

-9.3 (-16.2, -2.4) | |

|

Placebo |

96.2 (17.7) |

-19.2 (3.0) |

-- |

SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error; LS Mean: least-squares mean; CI: unadjusted confidence interval.

1. Difference (drug minus placebo) in least-squares mean change from baseline.

2. Doses that are statistically significant superior to placebo.

3. Doses that are statistically significant superior to quetiapine 50 mg BID.

14.2 Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episodes

Adults